12. Flora and Fauna as Art: A Contemporary Art Conservation Approach to Living Systems

- Sherry Phillips

- Sjoukje van der Laan

Intentional inclusion of living materials in art exhibitions is not a recent development. Records indicate that the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) was working with artists fifty years ago to display artworks with living components in its exhibition spaces. For conservators, trained as they are to slow down or even stop deterioration processes, an artwork’s intent regarding change or decay, both physical and conceptual, can pose a challenge. Responses to the conservation of contemporary art are often outside traditional conservation approaches. For clarity in communication with colleagues, the authors of this paper have developed an approachable decision-making framework to guide exhibition team members operating in an increasingly collaborative work environment and dealing with the unique challenges presented by artworks that contain living matter.

Our approach to these artworks has been dynamic; we are actively involved in the logistics of artwork and exhibition development, including health and safety, ongoing maintenance, and long-term preservation of the artwork. Can we better define our role to foster improved conversations with colleagues and create an evolved description of responsibilities? In the spirit of interdisciplinary approaches that lead to innovative ways of working, we have been exploring the role of a dramaturge in the performing arts to refine our evolving role in the conservation and preservation of contemporary art.

Brief History of Living Art at the AGO

Any natural process, I think, eventually destroys itself. Even if you do a painting, destruction is an element in it. Everything grows, blossoms and eventually dies.

—John Van Saun, 1969

Living matter in art installations at the AGO began at least as early as 1969 with the organization and installation of the exhibition New Alchemy: Elements, Systems, Forces (fig. 12.1). The artists Hans Haacke, Charles Ross, Takis, and John Van Saun were selected by curator Dennis Young for their work with the physical, chemical, biological, and ecological aspects of earth, air, fire, and water (). Following New Alchemy and its inclusion of growing grass, hatching chickens, and bread mold, the AGO installed Realism(e)s Survey 70 the following year. Did You Ever Milk a Cow? (consisting of a cow, its enclosure, painting, straw, feed, water, plus the cow’s other requirements) by artists Glenn Lewis and Michael Morris was installed indoors and featured Elsie, a local Jersey cow (fig. 12.2). And just over a decade later, in 1982, the AGO again hosted an installation containing living matter, in this case works by Noel Harding, an artist known for video, installations, kinetic sculpture, and public art. Chickens, a tree, and goldfish were all living components of Harding’s solo exhibition ().

Figure 12.1

Figure 12.1 Figure 12.2

Figure 12.2The AGO archives contain limited documentation, of varying thoroughness, from the artists or their associates regarding the care and maintenance of these flora and fauna. What conversations took place with them about the planning, installation, health, welfare, and safety of the living art, staff, and visitors? It is likely that these communications happened, but were not documented. Without contemporaneous records to guide us or artist’s studio records to consult, we can only surmise the installation requirements. As noted by Stefan Michalski in Modern Art: Who Cares?, contemporary art objects are especially vulnerable to memory loss (, 294). Until 1984 there were only two staff members in the AGO conservation department, both focused on traditional paintings, sculpture, and works on paper; they surely had very little, if anything, to do with the planning, installation, or maintenance of the living artworks.1

The cultural and institutional context of an installation should include the perceptions, observations, and experiences of not only the curator, the artist, and the many individuals who pack, handle, install, maintain, and even visit the work but also the documentation produced by conservators.

Case Studies

Within the last five years, the AGO’s contemporary art conservators have been working on four major contemporary artworks in the collection involving biological materials or living systems. Lessons learned from past living art installations underscore the need for careful documentation. All of these artworks are unique and demand an individualized approach to development and preservation.

Ron Benner’s Anthro-Apologies (and the trees grew inwards – for Manuel Scorza) (1979–80, fig. 12.3) was acquired by the AGO in 1994 and first installed shortly thereafter. Fortunately for us, generous documentation was assembled at that time. The work includes four gelatin silver prints (two on the floor and two on the wall) that have been enhanced with photo-oil colors. Textiles, vintage newspapers, a variety of small objects of various materials, dried and fresh fruits, vegetables, seeds, and plants are arranged on top of the two floor photo panels. Desiccation and decay of the fresh produce is intentional and part of the artwork’s concept. Fruit flies, sprouting seeds, mold, and decay are desired and part of the active nature of the work.

Figure 12.3

Figure 12.3Although notes from the 1994 installation indicate an acceptance that the photo panels may be damaged by the natural processes of organic decay, and reprinting of the photos is authorized when necessary, the artist adjusted this statement during the most recent installation in 2016. Benner now prefers to preserve the original photo panels with as much of the original image layer as possible intact, complete with existing localized areas of damage. Preservation of “how it is now” has become the new benchmark. Replacement of one or both of the photo panels may still be considered an option when 50 percent of the image has been destroyed by the natural decay processes. Time and reflection, supported by past conservation documentation, probing questions, and open conversation, helped to refine the artist’s expectations and our actions.

Pierre Huyghe’s Untilled (Liegender Frauenakt) (2012, fig. 12.4) utilized the fabrication labor of honeybees to build a wax comb around the head and shoulders of a concrete reclining female nude sculpture. Coauthor Sherry Phillips was involved in the early conversations about the acquisition of the work and was able to engage in research to help guide the acquisition process.

Figure 12.4

Figure 12.4The import of bee and bee products is strictly regulated by the Ontario Ministry for Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs Bee Act.2 The Huyghe studio was prepared to send a completed sculpture to Toronto, but inquires to the relevant Canadian government agencies governing animal product importation revealed that it would not be allowed into the country. The AGO received the concrete sculpture and separate base and began to develop the wax comb head and shoulders in Toronto with the assistance of a local urban beekeeper and a hive of Ontario honeybees. The health and welfare of the living beehive was foremost in the plans to create the sculpture; the Huyghe studio and AGO staff wanted to be able to demonstrate that their approach took the health and welfare of the bees seriously. (With increased emphasis in the media on the challenges faced by bee populations worldwide, visitors do ask about the humane treatment of the bees.) Once the sculpture was considered complete, the bees were transferred to a new hive and the artwork was brought into the museum building to become a static object, inactive, with no live bees.

Simon Starling’s Infestation Piece (Musselled Moore) (2006–8, fig. 12.5) is a low-carbon-steel cast sculpture covered with mussels. To create this artwork, the steel sculpture was immersed for eighteen months in Lake Ontario specifically to become colonized by thousands of zebra mussels, a non-native invasive species in the Great Lakes region. Biologists at the University of Guelph and conservation scientists at the Canadian Conservation Institute and the Canadian Museum of Nature, who are experienced with shells and corroded marine metals, respectively, helped to formulate a plan to achieve the desired appearance and understand the potential aging expectations of the materials. As with the Huyghe piece, the components of this sculpture transitioned from active to inactive when it was brought into a gallery environment.

Figure 12.5

Figure 12.5The AGO’s most recent contemporary acquisition of an artwork with living matter is Today We Reboot the Planet (2013, fig. 12.6) by Adrián Villar Rojas. This room-size installation consists of a wide variety of materials, among which are plants such as sprouting garlic, potatoes, and grasses. Villar Rojas studio representatives were present during the first installation of the artwork at the AGO to guide us through the importance of the physical appearance and conceptual aspects. Most notably, the sprouting plants should appear to be struggling to survive in their postapocalyptic museum-like display.

Figure 12.6

Figure 12.6The installation opened at the AGO in December 2019 and is expected to be on view for at least two years. Close collaboration with the artist’s representatives occurs on a weekly basis for the duration of the installation. The sprouting garlic, potatoes, sweet potatoes, and grasses are constantly assessed and replaced when necessary to maintain the desired conceptual context for the installation. A replacements garden is located in the AGO’s Conservation Department, partly for the practical reason that we have windows, and partly because we were the only department equipped to take on the responsibility for this part of the ongoing maintenance.

Active or Inactive

Each of our living matter case studies was discussed or defined through our decision-making model. We have found that artworks with biological materials or living systems can be classified as either active or inactive. As with every organic element in nature, biological materials grow, flourish, die, and decay. The process is expected but often follows its own timeline. We need to adapt to the pace set by the materials.

Active artworks have a continuous, changing living system; the life cycle may be crucial to the authenticity of the concept. Pip Laurenson posits that authenticity in contemporary art and artistic intention are better articulated as work-defining properties (, 9). The pieces by Benner and Villar Rojas, as well as Harding, Haacke, and Van Saun thirty and fifty years prior, exemplify active artworks in a gallery environment, whether they are micro- or macro-biological. Active living systems require a dynamic and unique approach to their maintenance; living and changing components define the artwork.

For example, the Benner has actively decaying fruits and vegetables, and the Villar Rojas has actively growing but preferably struggling plants. When the display period has ended, the living organisms are rehomed, or dried and preserved, or discarded, while the concept is retained to allow for re-creation at a later date according to documentation and installation guidelines. The Starling and Huyghe works are currently inactive; the sculptures have become more like traditional museum objects. Their living systems were once active but by design became intentionally inactive when the artwork came into the gallery environment. They will eventually be treated like a traditional artwork with a conservation plan based on the needs of the materials.

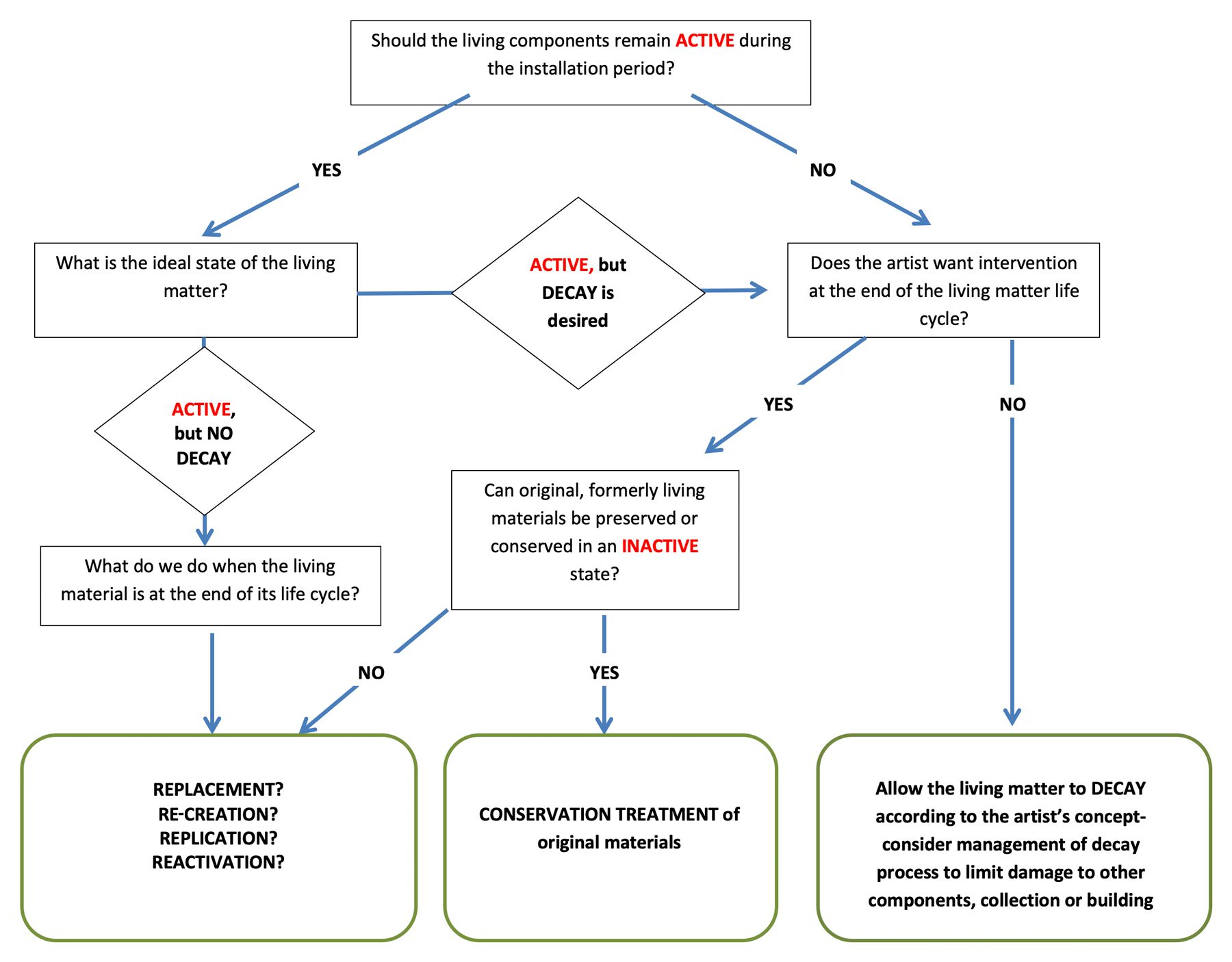

With experience gained through managing the many facets of biological organisms and artists’ concepts, we began to see patterns that guided us in the formulation of a flowchart (fig. 12.7). The flowchart assists with planning, installation, and maintenance of an installation in the context of a busy institutional schedule, but also supports communication of a structure and strategy for these nontraditional contemporary artworks to others who are involved in an increasingly collaborative process.

Replacement, replication, or reconstruction of component parts may be part of the conservation strategy for active or inactive artworks containing living systems.3 This contemporary strategy may be as simple as replacement of a handful of dislodged mussel shells to fill in an area that requires visual or physical support during consolidation treatment, or as extensive as reconstructing an entire wax comb with a new hive of bees when the artist determines that the comb (if or when irreparably damaged) no longer represents his vision. Replication may also be a strategy when components age or are lost, for example when a sprouting potato in the Villar Rojas installation deteriorates to the point that replacement is necessary to replicate the artist’s original intent (, 2).

Working through the flowchart, replacement, replication, or reconstruction strategies can be aligned with or equivalent to traditional conservation treatments, but also equivalent to sanctioned decay. Conservation of contemporary art is a productive activity, based in traditional practice but including interpretation and even coproduction of the artwork (, 252).

Secondary living systems may appear within the intentional living systems. In Benner’s case, he appreciated the need to manage fruit fly populations but preferred to not altogether eliminate their part in the natural decay process. His thoughts on mold growth were similar, but he left it for us to decide and act as necessary if mold growth posed a hazard to the health of staff and visitors. Our strategy was ultimately to manage the decay of fruits and vegetables with camouflaged absorbent pads to reduce the impact on the original photo panels.

While on open display at the AGO, Starling’s Infestation Piece (Musselled Moore) developed an infestation of webbing clothes moths (Tineola bisselliella) that were attracted to desiccated mussel flesh. The infestation put other works in the collection at risk and necessitated intensive treatment, first to eliminate the moths and second to restore the mussel array. The continued vulnerability has also led to artist-supported restricted loan status and the creation of a permanent display case for the sculpture.

The Huyghe wax comb still contains organic matter that cannot be cleaned away; it will be vulnerable to unintended occupation by other living systems when displayed without a case at the AGO. Its installation plan includes establishing an emergency infestation response.

The Villar Rojas work has to date been pest free. Atypical pests in gallery spaces such as fungus gnats in the garden in the Conservation Department and grain mites on bread components can be resolved with simple proactive monitoring and cleaning, but they are not desired auxiliary active living systems, nor are they harmful to other artworks in the vicinity. We work closely with the artist’s studio to manage the living components’ decay, knowing that the form and rate of decay is only revealed once the installation is living within our specific gallery environment.

Collaboration and the Role of a Dramaturge

Knowing the intent and establishing tolerances regarding how far components may deviate from the artist’s original intent assists in the determination of if and how we act, replace, replicate, reconstruct, or preserve an artwork while keeping its appearance and conceptual intention animated. Careful and extensive documentation is vital, as is close collaboration with many different colleagues and stakeholders for a successful resolution to a project incorporating living systems. This includes the artist and their studio as well as AGO staff such as installers, curators, and technicians, along with external professionals such as biologists or engineers. Being open-minded, thinking laterally, and persevering through challenging installations is increasingly part of our job. Experts external to the gallery and continuous collaboration and conversation are all tangible elements in the appropriate presentation of contemporary art with living systems.

We gather together divergent expectations and information and mediate between what might be best for the artwork and potentially conflicting institutional expectations. As members of exhibition content and installation teams, we also try to think ahead to potential conflicts with visitor and staff safety and security concerns. In order to determine that how and what we do to install an artwork meshes well with existing procedures, it is convenient to have a model to describe how our work could fit within the larger context. Vivian van Saaze in Installation Art and the Museum: Presentation and Conservation of Changing Artworks () provides an excellent discussion and overview of several individuals who have thought deeply about authenticity and artistic intent, and the evolution of how conservators work with and maintain the notion of authenticity in contemporary art. Performance theory, and dramaturgy in the theater arts in particular, has become a useful way for us to describe how and what we do with some works in the contemporary collection.

A dramaturge can have many different roles, but essentially they ask questions and start conversations in the development of a theater performance. It may be described as an exploration of the context in which a performance resides (, 64; ). Customary roles often come into clearer focus through the perspective of someone outside the familiar museum world. Dramaturgy was first mentioned to Phillips as she was working with a Toronto artist, Seika Boye, who was in residence at the AGO in August 2018. Boye’s project, This Living Dancer, is a self-archiving exercise that examines her evolving life in dance performance.4 During one session, as they prepared objects from Boye’s personal archives, exchanging questions and conversations as a working partnership, Boye turned to Phillips and exclaimed, “You’re a dramaturge!” The idea of a conservator proposing creative and pragmatic solutions within a museum and/or archival context to help the artist refine concepts for an installation seemed to Boye very much like the definition of a dramaturge.

The contemporary art conservator’s role at the AGO has evolved since the position was first created in 1984. Alongside repairs or restoration, we tend to be primarily responsible for establishing, fostering, and actively maintaining appropriate physical care within the context of authenticity and the larger environmental needs of the work. Like a dramaturge, we are accustomed to guiding an artist by asking questions, listening to their answers, and then negotiating with a larger team to find practical, achievable means of authentically realizing their work.

Conclusion

When an artwork contains living matter, a conservator can utilize a decision-making framework to establish whether the work is meant to be inactive or active, and from there develop a suitable animation or preservation strategy. The physical artwork is not always a sufficient guide on its own to create the preservation or maintenance plan. Decaying biological materials each have their own rate of change, which depends on local environmental factors such as light, relative humidity, and temperature. Conservation of contemporary art may diverge from traditional and established conservation concepts; for example, acceptance of material loss or replication may be part of the strategy.

Conservators must be involved, from the earliest inception to the final deliberations, in care and maintenance. Our practical knowledge of materials and processes does not have to be prescriptive. Documentation and close collaboration with the artist and their studio is essential to determine the necessary baseline of desired visual and conceptual appearance and atmosphere, now and in perpetuity. A conservator not only takes care of the physical aspects of the artwork, but may also act as a mediator between the various stakeholders involved in the work’s creation, installation, and preservation. How we define and improve our role in the process can come through other fields that have already established a similar role, for instance the role of a dramaturge in the theater arts.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to the Michael and Sonja Koerner Fund for Conservation Initiatives for its support of Sjoukje van der Laan’s participation in “Living Matter: The Preservation of Biological Materials Used in Contemporary Art / La Materia Viva: Conservación de materiales orgánicos en el arte contemporáneo” and ultimately our inclusion in this publication. We also thank Marilyn Nazar, AGO archivist, for her keen research assistance.

Notes

Ralph Ingleton, personal communication to Sherry Phillips, July 2019. ↩︎

See the organization’s website, http://www.omafra.gov.on.ca/english/food/inspection/bees/apicultu.html. ↩︎

discusses the concepts of replacement, replication, and reconstruction as part of contemporary art conservation are discussed. These papers were produced for “Inherent Vice: The Replica and Its Implications in Modern Sculpture Workshop,” held at Tate Modern, London, October 18–19, 2007. ↩︎

“Seika Boye Will Move You,” AGO Insider, February 4, 2019, https://ago.ca/agoinsider/seika-boye-will-move-you. ↩︎

Bibliography

- Cameron et al. 1988

- Cameron, Eric, Claude Gosselin, Rick Rhodes, and Ritsaert ten Cate. 1988. Noel Harding. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario.

- Cardullo 2005

- Cardullo, Bert. 2005. What Is Dramaturgy? New York: Peter Lang.

- Curtis 2007

- Curtis, Penelope. 2007. “Replication: Then and Now.” Tate Papers, no. 8 (Autumn): https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/08/replication-then-and-now.

- Laurenson 2006

- Laurenson, Pip. 2006. “Authenticity, Change and Loss in the Conservation of Time-Based Media Installations.” Tate Papers, no. 6 (Autumn): https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/06/authenticity-change-and-loss-conservation-of-time-based-media-installations.

- McCabe 2001

- McCabe, Terry. 2001. Mis-directing the Play: An Argument against Contemporary Theatre. Chicago: Ivan R.Dee.

- Michalski 2006

- Michalski, Stefan. 2006. “Conservation Lessons from Other Types of Museums and a Universal Database for Collection Preservation.” In Modern Art: Who Cares? An Interdisciplinary Research Project and an International Symposium on the Conservation of Modern and Contemporary Art, edited by IJsbrand Hummelen, Dionne Sillé, and Marjan Zijlmans, 290–95. Amsterdam: Foundation for the Conservation of Modern Art.

- van Saaze 2011

- van Saaze, Vivian. 2011. “Acknowledging Differences: A Manifold of Museum Practices.” In Inside Installations: Theory and Practice in the Care of Complex Artworks, edited by Tatja Scholte, Glenn Wharton, 249–55. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- van Saaze 2013

- van Saaze, Vivian. 2013. Installation Art and the Museum: Presentation and Conservation of Changing Artworks. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Wharton and Molotch 2009

- Wharton, Glenn, and Harvey Molotch. 2009. “The Challenge of Installation Art.” In Conservation: Principles, Dilemmas and Uncomfortable Truths, edited by Alison Bracker and Alison Richmond, 210–222. London: Elsevier.

- Young 1969

- Young, Dennis. 1969. New Alchemy: Elements, Systems, Forces = Nouvelle alchimie: Éléments, systèmes, forces: Hans Haacke, John Van Saun, Charles Ross, Takis. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario.