Keynote: In the Unpredictable Garden of Forking Paths

- Adrián Villar Rojas

- Sebastián Villar Rojas

Century follows century, and things happen only in the present. There are countless men in the air, on land and at sea, and all that really happens, happens to me.

—Jorge Luis Borges, The Garden of Forking Paths, 1944

I will approach the notion of “living matter” in two ways. One is the presence of material able to generate phenomena such as autopoiesis or auto-production in the “language games” () that I weave into my projects. The other is the presence in them of human work, or simply work, since, as the central thesis in the Marxist theory of value suggests, it is the application of “muscle, nerve, and brain” to transforming material that is at the core of human action on the planet. In effect, the human dimension is the primary “living matter” that, I believe, I have devoted myself to shaping, both in respectful exchanges with local actors and in the social experiment that my team has been and continues to be. It is these two directions (work along with my collaborators and the auto-production of organic material) that I will address in this essay, inscribing them diachronically in the evolution of a praxis.

2004: Year 0

If I had to choose a relative starting point for my dialogue with living matter, it would not be the direct use of an organic element, but a pictorial representation of life, namely the reproduction of two Jurassic landscapes by Charles R. Knight, who created the murals at the Museum of Natural History in New York, which I commissioned my friend and faculty of fine arts colleague Juan Manuel Hernández to produce for my first solo show, Incendio (Fire) at Nuevo Espacio, Ruth Benzacar Art Gallery, Buenos Aires, in 2004. In them, two dinosaurs graze and look toward the horizon on the savannah seventy million years ago, in a hypothetical scene from daily life in the Late Jurassic. The only difference, missing from the original and added by Juan at my request, is a handful of tiny trails of fire, almost imperceptible, in a corner of the blue sky: a group of meteorites that in just a few moments will trigger the start of a new mass extinction on Earth.

2006 and the Close Encounters Mountain: Anthills in front of the Elementary School

A man wakes up in the morning and hurries to his garden. He gathers soil in a wheelbarrow and takes it inside his house. He dumps it in the living room. He repeats this activity for days. He doesn’t stop until he has made a mountain with a precise shape and size: a homemade three-dimensional map of the place where the close encounter will take place. The scene changes the history of film.

It is the same obsession that pursues me: soil/earth. Wire structures covered in Kraft paper, coated in glue, and sprinkled with black dirt until they become a volcano, or actually an anthill. The theme of the alien runs through my drawings, my notebooks, the little projects that look as if they were made by a teenager, a nerd, a loner, at home in his garage. With these giant anthills, it is not the theme but the logic that produces them that seems alien, strange, alienated, emancipated from the “human.” Rather than content, it is an ontology that is glimpsed beneath the obsessive creation of those anthills: an exercise in distancing in order to produce material noise in the environment, silent entities that barge or burst onto the scene implosively like an autistic presence. There has been a photograph for years on the Wikipedia entry in my name: I am installing anthills in front of the door to an elementary school in Rosario during Art Week 2006, surrounded by students who look at me as if I were an alien consumed by a useless or incomprehensible task.

The mountain-anthills reappeared in 2007 at the Centro Cultural Borges and Belleza y Felicidad, both in Buenos Aires, eliciting the same sense of an autistic impact on the space, and ended up stored for years in my parents’ living room, crumbling on their carpet (fig. 0.1).1

Figure 0.1

Figure 0.12007 and the Map of Maps: The Petrobras Table

Pedazos de las personas que amamos (Pieces of the People We Love, 2007, fig. 0.2) is a twenty-meter-square table where, with countless materials and homemade processes, all of the cause-and-effect relationships needed in the multiverse for a tragically ending love story are put into play: she is infected with bacteria carried by a meteorite on exhibition in the forest, and he commits suicide inside his robot on the side of a mountain (made out of cake by my aunt, just like the ones she used to make for my birthday when I was a child). Nearby, another cake covered in green sprinkles serves as the base for a dinosaur lying amid balsa-wood crosses and little pastry trees. A school of goldfish swim in their world of glass and electrically oxygenated water. A canary song echoing snippets of Nirvana and Radiohead drifts from a PC’s humble speakers. And under the table, again, the soil piles up in a series of hills sprouting sepulchral crosses. The interaction of low-cost industrial objects (Chinese imports bought in the wholesale commercial zones of Rosario) such as articulated dolls, backpacks, decorative ceramics, costume jewelry, stickers, dishes, electronics, and Styrofoam packing materials is combined with this—somewhere between ominous and innocent—presence of the organic in a trans-temporal microcosm where every element in the chain of causation has not yet been destroyed by entropy—that is, by the arrow of time—and is therefore frozen in the instant of greatest productivity to be an explanation or consequence of their previous or future link. It is done in a way that reprises Antonio Campi’s The Mysteries of the Passion of Christ (1569), where Jesus is alive, dead, resuscitated, and ascending, not only in the same painting, but in an apparent single chronotopic unit: an Aleph with no chronology, or with a chronology that has been undone by its own exacerbation.

Figure 0.2

Figure 0.2That is where the first sculptures appear, in that whirlwind of three-dimensional stimulation, modeled out of two materials that are diametrically opposed in their durability: clay and epoxy. The raw clay figurines and objects will disappear in a matter of weeks once the project is dismantled. The epoxy ones (the busts of the tragic couple, for example) are still on top of the souvenir display case at my parents’ house, intact, like the youthful melancholy beauty of lovers.

Here, using the very temporal multidimensionality of the project, I will flash forward: the cake-mountain, made of four stories of cake, where the protagonist would go to commit suicide, will be returned to Rosario and stored in the warehouse of the family business along with other remnants of the Petrobras table.2 My parents kept it on a shelf for eight years until 2015, when, now practically reduced to dust, rock, and mold, it was moved to Sweden using a sophisticated logistical plan that spanned thirteen thousand kilometers. In Stockholm it was displayed in a specially designed case with ideal humidity and temperature conditions as part of Fantasma (Ghost, fig. 0.3). That project was an attempt to imagine what a retrospective of my oeuvre would be like two hundred years from now, given that because of its radical entropy, there would be nothing more than some residuals or remnants of its material form. We will get back to this point.

Figure 0.3

Figure 0.32008 and the Birth of Entropic Awareness

I used to say that the Petrobras table is a map of maps, a master plan for my life project, meaning that, in retrospect, one might see each of my subsequent steps as the hyperbolic development of a particular vein of work that was already present in that work and in the experience of producing it. This is absolutely apparent in Lo que el fuego me trajo (What Fire Has Brought Me, 2008, fig. 0.4), a hyper-entropic universe born from a particle of the Petrobras table: the clay figurines I mentioned above, barely noticeable among the myriad creatures that populated its surface like the multitudes of every species that teemed throughout Star Wars’ intergalactic Tijuanas.3 All I had left of them were five unused bags of clay, and the experience of making something that simply disintegrated.

Figure 0.4

Figure 0.4In January of 2008, I sank my fingers into the clay and started to model without any preconceived outcome. In a couple of hours, I imitated the life I saw around me: a jar of pills, an iPod, a spoon. I was in the first and only studio I have had, a house in Buenos Aires that I rented and lived in for two years. It was a first time for many things: living alone, away from Rosario, having a place to work, and the ominous imminence of grief that I would experience in March of that year with the death of my maternal grandfather. In a couple of months (once again picture the lonely, quasi-autistic adolescent, driven by an apparently useless obsession, a kind of calling from elsewhere, as with the unraveled time Kurt Vonnegut’s character experiences in Slaughterhouse-Five [1969], but unlike the catatonic state that character falls into when traveling to a parallel universe; my condition was still more akin to that of the compulsive man in Close Encounters of the Third Kind [1977]), I filled the house with a clay “memory” that was already starting to crack the minute I set it down on the shelves or the floor, wherever there was a place to put it. The clay interacted violently with the air, the temperature, the humidity, the vibrations of the noisy world into which the pieces were born to simply die, like Martin Heidegger’s Dasein. They were—I discovered—beings conceived to perish.

Like the condensers that Nikola Tesla conceived to transform the electromagnetic waves that surround us into instant energy, these humble raw clay Daseins were hypersensitive to time. They absorbed it from every particle that came into contact with them, accumulating and amplifying it. They magnified it thousands of times, as if under a microscope lens: that lens was their very body, which cracked and aged in just a few hours until it was transformed into a fossil, before disintegrating and vanishing. For me, then, clay represented the possibility to fossilize beings, whether figurative, abstract, or symbolic. There was one step between this discovery and playing with the oxymoron: the future (incarnated in a cyborg, in a device for the digital era, or however our imagination represents the future) can be fossilized until it becomes a cemetery of what is to come. And at the same time, what is clay but the prehistory of life on Earth, organic matter pounded into infinity, the sediment of everything that has lived on its cool shores or beneath the surface of its waters? The remote past and the distant future draw closer to the present, and the present distances itself with them or opens up to its othernesses (to the multiverse, to its parallel dimensions). With clay, time becomes manipulable. Time becomes sculpture. And sculptures become suicidal.

From Time as Sculpture to Time as Sculptor: Moving from Suicidal to Diachronic Objects

I began to multiply these clay entities dramatically in 2009. It started with the whale at Parque Yatana in Ushuaia, Argentina, for the Biennial at the End of the World (fig. 0.5).4 There were key moments, like the eleven monoliths at the 2011 Venice Biennale, the hundred-meter cylinder at the Tuileries Garden in Paris, also in 2011, or the sculpture forest at dOCUMENTA (13) in Kassel (2012).5 These projects condensed all the ideas laid out above: noise or estrangement from the landscape; the radicalization of time as representation or narrative; a distancing from the human world through its fossilization; and hyper-entropy that annihilated objects that were ever more labor-intensive because of their magnitude or complexity.

Figure 0.5

Figure 0.5Adding to that, on the one hand, there was an increasing defiance against the limits of the field of “art” (the variables that ensure that its reproduction and even its transformation into a commodity—transport, durability, scale, costs—were continually mined or taken to the extreme, first in a more intuitive way, and then in a more systematic and conscious way, which I will call “the philosophy of limits”). On the other hand there was the birth of a community of collaborators that embarked on its own path of development vis-à-vis clay, expanding its possibilities as a material while improving strategies and accumulating knowledge and technology. Here, clay begins to turn into a language that is transferable to future generations. Each new collaborator internalizes and tests the techniques, the processes, the group dynamics, all of which vary from project to project. Sometimes the serial and repetitive logic of the factory comes into play; at other times, it is the creative and loose logic of the artisanal workshop; and at yet other times, it is the harrowing and uncertain dynamic of the experimental laboratory. I am always the coordinator of these metamorphoses, generating different communication dynamics with each team member, at times more transparent and direct, and at other times more opaque and ambiguous. No one person is the same, and no one person requires the same thing.

From the language of engineering to the language of psychoanalysis, from the prompt to Socratic catharsis, from Frederick W. Taylor’s assembly line to Melanie Klein’s negative transference, the discourses that spark ideas in the studio are numerous, hybrid, mixed. I try to take maximum advantage of the gaps in communication (misunderstanding as a source of discovery, as a space for creative freedom), but also of the possibility of establishing very strict codes when necessary. In short, the “community” engages in a dialogue with itself and with its surroundings in the hyper-specialized language of raw clay. Over time, cement was added to it, leading to the mixture that would dominate the period between 2008 and 2013: clay + cement. This formula also signals a key metaphor in my practice: “before human beings” + “after human beings”: the traces of life before the Anthropocene (clay) and the traces of our lives in its wake (cement).

What began in 2009 with the two collaborators I found in Ushuaia based on recommendations from locals, César Martins and Mariano Marsicano, and Alan Legal, a technical assistant I brought from Buenos Aires, became Today We Reboot the Planet (2013) in an enormous warehouse on the outskirts of London.6 This is an organized system with workstations (self-designed mini-studios), where more than ten collaborators function as actors on their own sets (jewelry, sculpture, construction, metalworking, et cetera), improvising their roles based on interactions with a director (me), who shapes their performance in real time, reacting to each of them based on what they provide and building their scenes along with them. The material results of this process of “rehearsals” come together in the “premiere”: the opening of an exhibition, which is increasingly less satisfying or representative to me as a mechanism for the visibilization of work, given its complexity. The actual richness of this process—the intense human activity, the living matter of the theater (muscular and neural energy put into play)—has disappeared forever. The resulting pieces barely bear precarious witness to what is no longer there, namely the life of a community developing a language over weeks or months. To survive, that community has become nomadic—an itinerant company that, even as the current exhibition is opening, is already flying to its next destination.

As projects pass by, I am more and more aware that human experience is the lost core of my practice and that physical material is just evidence of it. It is no longer just about the idea of a suicidal materiality that, over time, won’t leave more than a trace of itself, but about the very idea of materiality (no matter how many centuries it lasts) as residue, as remnant, as an utterly insufficient record of a life that is always a fleeting present. The stage metaphor takes on its full meaning in that the theater is a perpetual dueling ground. In every performance, the “play” is born, lives, and dies. It is human activity in a continuous present, and it is only in acting out that loss that the next performance can be accessed (which will also lead to a next death). No record (audiovisual, written, or oral) can supplant shared experience. The bodily ritual that exists between actors and spectators is structurally irreplaceable. That logic somehow runs through my own praxis, the “disappearance” of which becomes less about the material than about the human hand that works with it.

Two other changes in London are connected with a space that has been operating in Rosario since December 2012, the Brick Farm (fig. 0.6). It is an experimental open-air camp installed in a corner of a lot belonging to an artisanal brickworks on the outskirts of my hometown, in a transitional area between rural and urban environments. Members of my team work on a variety of activities there, mainly testing materials (looking for greater stability in combinations of clay and cement), exploring the surroundings to gather organic materials or “residuals,” and exchanging knowledge and experience with the workers at the brickworks, who utilize the same traditional methods used for more than one hundred and fifty years to produce adobe bricks. This experience yields surprising results, opening new horizons in experimentation with highly unstable organic materials, from vegetables, fruit, legumes, and plants to even small animals that are found decomposing near the brickworks (fig. 0.7).

Figure 0.6

Figure 0.6 Figure 0.7

Figure 0.7It also leads to an encounter with a species of synanthropic (highly adaptable to human environments) bird and its peculiar architecture: the hornero bird, a national symbol, and its nest, which resembles a traditional domestic mud oven used to bake bread in rural Argentina (fig. 0.8). I discovered that this bird, the brickworks, and my team all share the same material as object of transformation: soil. Each has their own methods and techniques to manipulate it, shape it, and stabilize it, but all have the same goal: to build with mud. In one case, cow intestines bought from local slaughterhouses are dumped into a giant hole filled with dirt and water, where a herd of horses trample it all until the mix is blended to make adobe (mud blended with the dung from those intestines), which is then dried in rectangular molds and fired in pyramids made of those same raw bricks (fig. 0.9). In the other, the adobe is fashioned by making a ball in the beak, blending saliva with bits of straw, branches, and grasses gathered in the area as the ovaloid walls of the nest are erected. And in the third, mud is blended with cement, wooden structures, screen, and wire.

Figure 0.8

Figure 0.8 Figure 0.9

Figure 0.9The Paths Fork: The Hornero Nests Series as a Kind of Departure from Brick Farm

The horneros make use of the technologies and resources of the Anthropocene, building their nests not only in tree branches but on utility and telephone poles, building facades, window ledges, air conditioning and ventilation units, urban traffic lights, and pretty much any other opportune spot to serve as the foundation for their construction. The birds use the nests for just a single reproductive period, abandoning them once their offspring are ready to fly. Veritable abandoned residential complexes, sometimes with five or six units stacked atop one another, grow silently in the cities and towns of the Argentine Humid Pampas. You only have to look in the right spots to find them. My collaborators did just that. They began to track down and gather these abandoned nests from the brickworks’ surroundings, instantly associating them with their own work as sculptor-builders. The team started using them in different experiments with clay and with the artisanal firing techniques of the brickmakers. It was the start of a project with no temporal or territorial boundaries: to expand the architecture of this unique South American avian species across the planet.

I started installing these nests in different places around the world: New York (2014), Kalba, UAE (2015), Stockholm (2015), Havana (2015), Anyang, South Korea (2016), Riga, Latvia (2018), Drenthe, the Netherlands (2018).7 I used the hornero’s own construction and installation logic, and stimulated a dialogue not only with other regions in the Anthropocene but also with other species, because those nests often serve as shelters for different creatures, for instance snakes, mice, and other kinds of birds. I make use of institutional opportunities like the Havana Biennial or the Riga Biennial. Cities and towns become the stages for an invisible, silent project whose protagonists are for the most part not human, but the small animals and insects that occasionally inhabit the nests. For the people who see them, these ovoid mud forms, which remain indefinitely on building facades and light posts after the “event” they were a part of ends, become a kind of curiosity in the landscape, unlikely to be seen as art.

This liminal state—the integration of these objects into the environment and the refusal to identify them as fetishistic objects protected by a field and an artist, instead letting them become things that exist autonomously—is an exploration that has been systematized in the series titled Brick Farm. Nonetheless, it has other very significant moments, like the whale constructed in the San Juan desert of northeastern Argentina in 2010 and “found” by a drone in 2017, when technology could finally access this inhospitable place. Area newspapers and social media spread reports about the discovery of a fossil of an unidentified animal, possibly a prehistoric cetacean that lived there when the Andean mountain range was dominated by the ocean. The emancipation of the thing, which is not even from this geological era, dumped onto the world completely naked, seems to me the highest aspiration for a work of art: to simply stop being one.

Rosario Inseminates London: Brick Farm in Today We Reboot the Planet

Ariel Torti became a key player in Brick Farm, the open-air experimental lab at the brickworks in Rosario. His upbringing in an agricultural area of Argentina gives him an understanding of rural matters that he puts to use at the brickworks. He knows gardening, horticulture, and botany. He is the main force behind the germination and hybridization experiments with potatoes and beans. He composts all the organic matter he comes across, and grafts plants and legumes with vegetables or tubers. He will allow life to take its course in the fierce heat of the Argentine summer, which in the central littoral region can easily reach temperatures of 40ºC (104ºF). Everything emulsifies, grows, fills with mold; forms burst forth within forms. It is a biological kaleidoscope unfolding before his very eyes, while he paints hornero nests with clay and fires them in artisanal brick pyramids.

When the team left for London to start work on the project at Serpentine Gallery in July 2013, Ariel remained at Brick Farm, where he continued working for six more weeks. He has become a fixture there—or, more precisely, he is the Brick Farm. So when he lands in the British capital, one month after the others and dealing with administrative delays for permissions to enter the studio, he is far from being slowed down or paralyzed. He begins to carry out his experiments with organic materials in the house where we all are staying. He goes out on long exploratory walks in the area that generate a haul of found materials and photographic records. Excited, he sends me emails telling me and showing me what he is doing. It dawns on me that Ariel has arrived in London, but he is still in Rosario at the brickworks. He has brought his logic and dynamics to the English metropolis. So, I propose that he makes a psycho-dramatic experiment: to become Brick Farm, to absorb that project in his own body, and have a dialogue with the project we are engaged in there, no longer as Ariel, but as this topographic character.

From that moment on, I communicate with Brick Farm through a continuous exchange of emails. We reflect, ramble, and share impressions about his botanical and horticultural experiments. He is taking his search in the landscape for “things” even deeper, from trash, knickknacks, textiles, and other industrial items to vegetables, tubers, fruit, edible animals, seeds, flowers, legumes, and plants. He grafts beans onto a watermelon, fills it with clay, plants it in the backyard of the house. He buys a shoe, fills it with dirt, plants sunflower or flax seeds, and inserts a chicken liver. He is completely obsessive. He photographs everything he is doing and writes about it cryptically, almost illegibly, in his accounts sent via email, which I respond to in an utterly natural way.

When Brick Farm is finally in the studio, it is ready to start a revolution at the workstations: its mission is to provoke them, to be a parasite, to introduce anomalies, like a satellite off its orbit that uses the orbits of functioning satellites not to reestablish its own, but to drive the whole system mad (fig. 0.10). Basically, living matter, in a state of decomposition or growth, penetrates every worktable. It blossoms, flows, gushes forth; it settles in between the spaces of the materials it intervenes in, whether inorganic, like plastic or metal, or a more stable organic ones like wood. Each variation incorporates fauna and flora. Even the lunch leftovers are transformed into a source: the waste matter is reintroduced into the process as a destabilizing mechanism. Everything is convulsing.

Figure 0.10

Figure 0.10A pair of pliers suddenly disappears and reappears lodged in a sculpture at another station, almost like an act of vandalism, and sparks a new logic in the pieces. The studio enters directly into the final product as metonymy (a tool becomes part of the object, sticking to it like a mushroom on a humid surface). The borders between workstations, supplies, materials, waste, people, and “artwork” blur without disappearing, but stretch in their capacity to offer certainty and order. The situation becomes barely tolerable. The system tries to immunize itself; there is contact and friction; there are attempts to expel the foreign object. Where there is life, there is the struggle for survival, but also cooperation, dialogue, politics. Brick Farm questions, using the discourse of a psychotic person or an analyst. For this intrusive character, the stations become plots of land displaying a twisted agriculture of symbols that, through the living matter, continue with their unpredictable contortions.

The parasitosis soon bears fruit. The jungle cracks the cement—or in our case, cracks the “clay + cement” formula, whose painstaking development inside that “community” of sculptor-builders has led to increasing stabilization, a programmed disappearance, a controllable instability that is exhausting its revolutionary power. There is a need to dynamite the ankylosis and introduce new processes that cannot be manipulated by complex wood, wire, and steel mesh structures, the way the clay ultimately is. That same clay that fell apart in Ecuador during a storm the day before the opening at the 2009 Cuenca Biennial, leaving nothing of the piece behind but photographic records as the water and wind demolished it, is now the material base for an organized community that is highly developed technically and symbolically, and able to transmit its structure from one generation to the next.8

It is no coincidence that cement, the crust that the Capitalocene (the geological era that corresponds to capitalist modernity) will leave behind long after we disappear as a species, came to consolidate this order of things. It represents, in my praxis, the redesign of the planet for and by human actions. After five years (2008–13) the clay + cement equation has reached its greatest degree of operational and semiotic equilibrium. Through this clay + cement period, the phase of time as sculpture—as a narrative with its relative center in that human action—is coming to an end. It will make way for time as sculptor, and for nonhuman agents as the protagonists. The time has come for one cycle to end and another to begin, starting with intense work of micropolitical, micro-poetic, and micromolecular sabotage. This political-poetic-material agitation has at its core Rosario’s insemination of London, of Brick Farm in Today We Reboot the Planet. The result will be the transition from programmed suicide to deprogrammed auto-production—from suicidal sculptures to diachronic, mutant, or hybrid objects.

From Programmed Disappearance to a Deprogrammed Auto-Production

What we have in Today We Reboot the Planet, then, is this world interfered with via sabotage, negotiation, and resignification operations by the satellite Brick Farm, the character-project-place that injects an “anomalous” logic, as Thomas Kuhn might say, into a “normally” functioning planet (). This saboteur’s chemical weapon is, on the one hand, the organic material collected in situ, and on the other, what we can call the insemination of the different contextual levels within the microcosm of the workshop (including the workshop itself as the last of those levels, from the atomic perspective of the workstations). This takes place through Ariel Torti–Brick Farm’s exploration of the project’s urban environment (London) and the pollinating act of circulation among the different stations, just as he/it did in and around the brickworks in Rosario. While the workstations are already engaged in a dialogue, their communications are catalyzed by this “bee” until they are transformed into an authentic hybridizing force—a genetic mutation.

When the planet reboots, it will find its whole system reconfigured. The echo of a world at once in silent agony and in continuous transformation will appear on the specially designed shelves, as if in an alien warehouse, inside the new Serpentine Sackler space (a former gunpowder store repurposed by the institution, and now also adulterated for this project by my team of architects). Potatoes, onions, apples, mushrooms, beans, leaves of plants, all of that still-timid life that is now woven into the “suicidal sculptures” germinates, grows, rots, dries up, attracts more life—insects, bacteria, microorganisms. It radicalizes a logic that will be key from this point forward, namely the openness and plasticity of the “object” that becomes a porous system in permanent interaction with the environment, yet with more morphological possibilities that are less predictable, while the incorporation of new biological structures multiplies the diversity of behaviors and the physical-chemical reactions of its components.

It is not the greater instability, but rather the greater contingency and number of movements—the depth and complexity of the mutations to the point of dissolving the idea of “final form” on that of the “horizon”—that is released here as the core of the ontological revolution initiated within my practice in Today We Reboot the Planet. Thus, the final leap of variable time from the surface (as theme, as representation) into the interior of the modeling mechanism (as a sculptural force) is essential for redefining these new entities as diachronic objects. Their real wealth is not in the photograph but in film, in the comparison between two points in time. From one day to the next, from one week to another, from one season to the other, the mutant proffers observable changes. Of course, this dynamic was already present in the “suicidal” pieces, but its radicalization leads us firmly to the notion of autopoiesis, of deprogrammed auto-production. The various paths already existing in the garden have forked into hundreds of possible (and unforeseeable) paths.

The Theaters of Saturn: Anomaly as Law

In the way that the Phrygian cap used by freed slaves in ancient Rome became a symbol in modern European and American republics, anomaly became law in the project immediately following Today We Reboot the Planet, titled Los teatros de Saturno (The Theaters of Saturn, 2014, fig. 0.11, fig. 0.12, fig. 0.13).9 In Mexico City, the out-of-orbit satellite is the locus of a new orbit of processes, operations, techniques, directions, and detours. Everything that was insinuated conceptually, experienced as a team, and accumulated as a technical and methodological legacy at Serpentine is transferred, expanded, and legitimized at kurimanzutto gallery. On one hand, the mutants take center stage, and the Brick Farm devices now become a work structure, a way forward based on exploration of the environment. This is the core mechanism for obtaining local materials and knowledge that will be hybridized on the nomadic studio’s worktables. This studio in Mexico City is turning into a mutant garden, a nursery for monsters, where the workstations do not disappear but instead subordinate themselves to this logic, providing the other key ingredient in the combination (the products of collaborators, like Mariano Marsicano in his role as jeweler, or of Martín Pazienza as ceramicist) or momentarily shifting over to a second plane, as with those stations that are still subject to the rules of the previous paradigm and set to reproduce some pieces from dOCUMENTA (13). On the other hand, the system’s increasingly porous condition is visible in another aspect with clear antecedents in La inocencia de los animales (The Innocence of Animals, 2013), and even in Today We Reboot the Planet.10 However, now it is presented as a true dialogue with the environment, whereas before it was an imposing force. I am referring to the reformulation of architectural-institutional space with which the project interacts.

Figure 0.11

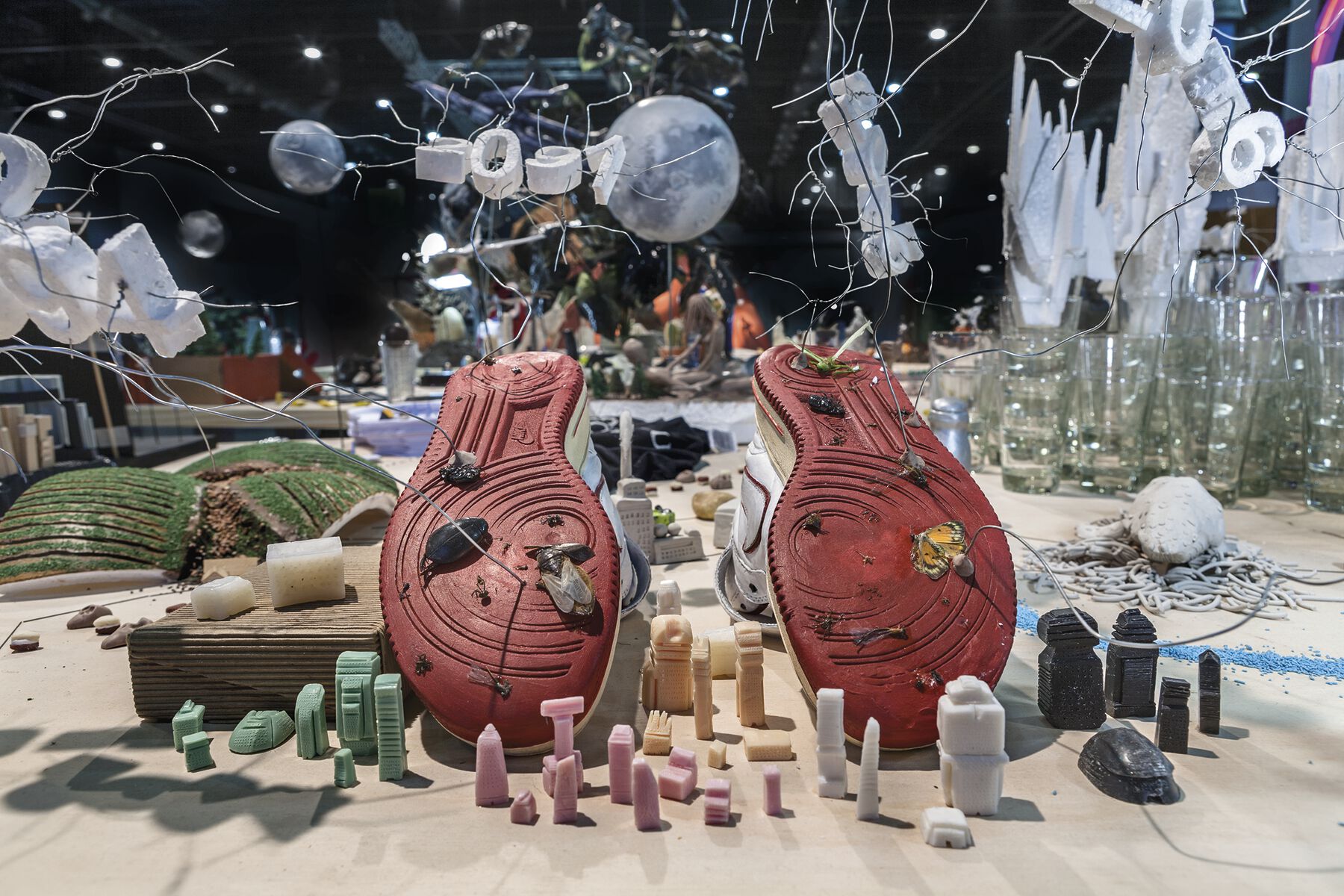

Figure 0.11 Figure 0.12

Figure 0.12 Figure 0.13

Figure 0.13In Los teatros de Saturno, the spaces at kurimanzutto are modified to house the mutants and the rest of the show. This includes an exhibition in the second story of the gallery in the form of a “3D fanzine” that features a considerable amount of the information about production and direction generated in the London project with its curator, Sophie O’Brien, who also comes to Mexico to work as another station on the team. This second story will thus be entirely devoted to serving as a kind of archive or record of Today We Reboot the Planet, with hundreds of emails, notes, sketches, maps, drawings, lists, and other assorted papers. In general, such things are either kept or discarded, but they are rarely exhibited, at least not in this way, namely as an artist’s subsequent project, highlighting the organic nature of the chain, the residual energy that passes from one project to another. It is one more way of forestalling death, of recovering the dense life that goes well beyond the possibilities of the visible. What can’t be trapped is clamoring to emerge and incorporate itself.

The surface of the ground floor is covered in soil, and the results of this mutant botany are planted in it. Ariel Torti–Brick Farm works on these hybrids along with two Mexican floral project and landscape specialists (AR COSMOS), who recommend exploration of the local markets: La Lagunilla, La Merced, Jamaica, the fish and meat markets, and the Central de Abasto wholesale market, among others. Expeditions to these commercial centers, either open-air or in giant hangars, jammed with vendors and customers offering and comparing merchandise, are decisive for the project in that they allow both the synesthetic impact of encountering a world of colors, flavors, smells, shapes, and even sounds to fill the work, and a myriad of materials without precedent in my practice, due to their variety and number: fruits, vegetables, seeds, legumes, herbs, mushrooms, flowers and ornamental plants, minerals, rocks, even antiques.

With the palette laid out on tables throughout a warehouse of more than five hundred square meters, and with very few tools (blades, spoons, plastic containers, hand mixers), the three “botanists,” Ariel, Alfredo, and Ramiro, begin to outline the various methods for intervening in, modifying, and arranging these mutants, added to by other stations that provide sculptures, jewelry, geometries in pigmented plaster. The ontological question I have asked in order to set up this game is: What would the world look like if it had to be re-created by this community of sculptor-builders? What would its fauna and flora, its fish, its insects, its fruit, its stones, its animals be like? Ultimately, what would the three realms look like after this team of “aliens” encountered it?

That is how a line of inquiry in my practice matured—one that was sustained from the beginning but is now very clearly defined. Human agency is replaced in favor of other agencies (bacteria, mushrooms, insects, climate, seasons, reproduction, growth, decomposition) that employ time to exert their influence to shape things. From the museological paradigm of protecting “things” against the passage of time, we move toward “things” that are “beings in time,” with pasts, presents, and projected futures, auto-produced but also conditioned by contextual variables. Thus, the institutions that house these mutants take on a central role. The hybrid’s “quality of life” depends on their control and monitoring, their care and interest, in conjunction with oversight by my office.

The Guggenheim in New York or the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris do not provide the same context as the one experienced by an object left at the Brick Farm, or at the Garden of Babur in Kabul, Afghanistan.11 Or at Eco Flor, an edible-flower nursery in Xochimilco, on the outskirts of Mexico City, which I visited with Ariel Torti and Noelia Ferretti after the opening of Los teatros de Saturno to continue our research, bringing with us all of the material that was left over from the project, including pieces that were not installed. This horticultural and agricultural region was central to the imperial Aztec economy. It supplied a million and a half inhabitants five centuries ago using techniques based on the artificial expansion of arable land, by building floating islands (chinampas) on the lake in the Valley of Mexico. We speak there with local producers, and intensify our explorations of the territory. We test and study methods with crops, landscape, and the local terrain. We end up developing two stratified cubes made of plaster, clay, and compost (fig. 0.14), which will become the basis of the next steps: The Evolution of God (2014), Where the Slaves Live (2014), and Planetarium (2015).12 This is how Brick Farm, as a praxis, develops its twin sister in Mexico, a kind of experimental farm in Xochimilco (where Ariel Torti additionally becomes the protagonist of a film that has yet to be produced). This farm signals the change of a period, the birth, from the womb of an anomaly, of a new law: the law of Saturn, the Roman god of agriculture, who managed to cling to his belt of seven rings, made of thousands of other rings. Those are the theaters of Saturn, which endlessly fork and give rise to new scenes and vicissitudes.

Figure 0.14

Figure 0.14The Project as System to Absorb the Environment, the “Cube” as Archetype, the “Table” as Map, The “World” as Territory (2014–present)

Everything in Los teatros de Saturno stems from the ecosystem where the project develops. Even the volcanic soil (tezontle) covering the floor is the result of an intense exploration of the region’s possibilities. We visit quarries, sand plants, and horticultural areas like Colonia San Gregorio Atlapulco, where we have access to an artisanal potato plot that will serve as the model to design the ground floor at kurimanzutto (the field of tezontle planted with mutants) (fig. 0.15). The local markets provide the materials that will be the biological basis for the hybrids, from tubers and flowers to crustaceans and fish. The local culture provides the poetics for the project: soil and color spontaneously emerge, with the latter returning after a six-year absence in the form of pigmented plaster. Through dialogues with producers, merchants, neighbors, and other key actors in the process, local lore and history provide the information and the images that bring specificity to the project.

Figure 0.15

Figure 0.15Geography, especially in Xochimilco, provides the territory to carry out a Mexican Brick Farm, and through it a dynamic of immersion in the topographical features of the environment. So powerful is the force that the landscape exerts on our senses—the diversity of the crops, of techniques, of species, of layers of sediment on the edges of the canals, of life fermenting within life—that the mutants become literally chronotopic (time-space) crystallizations, surfaces to absorb everything that surrounds us, like a screenshot of a dream, given the extreme metaphorical-metonymic concentration of these living entities. That is the case with those stratified cubes made of pigmented plaster, clay, and compost, which were born as a kind of multidimensional snapshot of Xochimilco. They are a material emulsion of our commitment with the site, the result of a state of interpenetration with the context, evidence in motion (since those cubes will remain at Eco Flor and be photographed in their diachronic transformation) of a fleeting present in a specific spot of the planet.

Ultimately, we have two levels operating at the same time in Los teatros de Saturno. One is micro, with the mutants, and the other macro, the project acting as a system of subsystems absorbing the environment. These two articulated levels render the ontological logic and the functioning of a new phase in my practice, where deep immersion in local contexts and the transport of vernacular material from one point of the planet to another to generate ever more complex hybridizations become the key to access future experiences.

A Pictorial Homage to Xochimilco

Inspired by the Xochimilco cubes, The Evolution of God and Where the Slaves Live are a “pictorial” homage to the change taking place in Mexico, where I set out to design, draw, and paint in 3D using the resources and techniques acquired in Los teatros de Saturno. In a way, this homage is a statement in which we lay out the rhetoric of a new poetics touched by that Mexican experience. This is why both projects enact a formalist play with stratification, the pigmented layers of sediment, the organic, the vegetation, blended with industrial detritus (sandals, textiles, ropes, bottles, personal items belonging to the team), which appear trapped in the mixture and which will lead various readers to see a metaphor with the Capitalocene. Both the “cube” in New York and the “tank” in Paris (fig. 0.16) are entities that replicate that autism of the early clay period (they are in some measure alien in the contexts where they are installed). But, like the project in Mexico, they return to the range of colors, materials, and elements of the Petrobras table, that map of maps where the dynamic of absorption of the environment was already implicit, on a scale appropriate to the period in which it was produced: everything that was used for the table was acquired through a process of exploring the commercial wholesale neighborhood of Rosario.

Figure 0.16

Figure 0.16The “tank” in Where the Slaves Live at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris is an example of the new institutional approach stimulated by this mutant dynamic. Its organic components and the growth of its vegetation require constant monitoring and exchange of information with my office, as well as daily gardening maintenance such as pruning, watering, et cetera, in order to keep its autopoietic drift under control. This is also the case with Motherland (2015) at the Guggenheim in New York, where I create a poetic gesture based on the institutional actions generated by taking care of the diachronic object. It is at once an eternal project and an incognito one on the building’s roof, a place inaccessible to visitors and only made visible by an annual “ritual” on the same day at the same time: a designated maintenance staff member goes up to the rooftop, walks around the walkway that circles the glass cupola of the rotunda, and opens a small square in the mesh ultraviolet filter that covers it, letting natural light through that opening into the museum for one hour. This ritual is not announced publicly, but instead is seen as an ordinary task, performed without any “artistic” sense. Installed next to the heating equipment in a corner of the rooftop is a small sparrow made of clay, viscera, twigs, and weeds. Its permanent exposure to the atmosphere means that it must be replaced at intervals established by the museum and my office, based on observation. Both the ritual and the object will be replicated under the same protocols until the institution is permanently closed in some distant or nonexistent future. Both dimensions of living matter that I am trying to grasp in this article (the interaction between human and nonhuman agency, between work and auto-production, and one could now add a third element: environment) are poeticized here in a silent system of material and performative gestures.

Transporting Material and Energy in a New Relationship with the Environment

The Most Beautiful of All Mothers (2015) and Rinascimento (Renaissance, 2015) are associated projects and represent a turning point in two issues: the connection with the environment and how to navigate the transition from one experience to another in a very short period of time, in terms of both the transportation of vernacular materials and the transfer of collective residual energy from one project/point on the planet to another.13 The Most Beautiful of All Mothers is a large-scale sculptural and aquatic installation (executed at sea) combining animals in a disorienting, absurd, or illogical way, for instance using some pieces as pedestals for others (fig. 0.17). Elements are also introduced that have been collected around the site, or from the store of transported materials or derived from the studio activities themselves that are unfolding in situ. The list includes fishing nets, livestock, scrap, clay, residue, minerals, and vegetation. It is a montage that makes use of the landscape as a kind of stage set, since these animals are installed on cement bases in the water, alongside the house where Leon Trotsky lived during the first three years of his Stalinist exile (1929–33) on the island of Büyükada in the Sea of Marmara facing Istanbul. The project demands very intense physical commitment, given, for example, the need to swim at night from one sculpture to the other to finish smoothing the cement at the bases and add finishing touches. It is a phenomenally transformative experience for us. Small sea snails soon appear on the parts exposed to saltwater, which triggers a fundamental question for me: What if this play of platforms, of animals holding up animals, has all of these tiny mollusks as the ultimate ending? What if this is only there for them to use?

Figure 0.17

Figure 0.17The more than two-month sojourn with my team in Turkey, which the production and assembly of these pieces for the Istanbul Biennial requires, leads to interactions with locals, from curators and producers to transportation specialists and suppliers. Some of those interactions result in lasting friendships. It also paves the way for a deep exploration of Istanbul—its marketplaces and landscapes, its geography and history and surroundings. During this process of exploration we collect vernacular materials, such as the one-meter-diameter stones to be used as the basis of the Turin project Rinascimento. Production on that project begins immediately following the opening of The Most Beautiful of All Mothers.

We arrive at this engagement enormously burned out and with no time to recover. The “community” of sculptor-builders, who have traveled the world as a tightly knit group, is threatening to fall apart as a natural consequence of exhaustion. The only alternative is to tap into that charged residual end-of-the-party or hangover state—to clean and organize the house the day after a big night. And that is literally what we do. The space at the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo is submitted to a housekeeping process. It is a dynamic that we will stick with from then on, with ever higher levels of awareness and conceptualization: the idea of domestic work as an activity generally assigned to women, with almost no acknowledgment or remuneration throughout history, yet vital for the rest of human activities.

With Rinascimento, we begin a diagnosis of the state of the physical and institutional space that will be impacted, with the understanding that the project should establish an ecological equilibrium with it. Based on this diagnosis, the process of deep cleaning of the operational terrain is deployed in order to clear these zones, unconscious of the accumulation of things, filth, deterioration, or chaos that institutions, through habit or negligence, tend either not to see or to normalize. Thus, in Turin, once the “semiotic noise” has been “weeded” from the building, we begin to set up the stones brought from Turkey (fig. 0.18). The almost psychoanalytical logic of diagnosing the overall state of an institution based on its spatiality and my possibilities of “cleaning” the excess of unconscious semiotic production enable me to explore an aspect of work that will take on a central role in my practice: negotiating with the authorities, or in other words the political dimension of the projects. In effect, the adjustment of the institutional environment to the ecological needs of the project will depend on a highly refined use of the “art of the possible.”

Figure 0.18

Figure 0.18Toward a New Human Ecology: The Geopolitics of Friendship

The convergence of ecological equilibriums that involve a strong empathetic and political commitment with otherness is manifest in El momento más hermoso de la guerra (The Most Beautiful Moment of War, 2014, fig. 0.19, fig. 0.20).14 This experience can be thought of as a third phase of Brick Farm, since it involves long-term immersion in a rural setting, this time Yangji-ri, a village in the demilitarized zone (DMZ) between the two Koreas, whose stable population has an average age exceeding eighty years. Here, the intention is to establish contact with residents from the very beginning in order to develop a film project focused on their lives, selecting some “characters” and encouraging activities that may trigger situations or atmospheres, such as a community lunch in which my team prepares a pig using the Argentine grilling technique of asado. In this way, without a script and giving in to serendipity, we are able to get takes in alleys, in the countryside, in the town church, in residents’ homes—ultimately a range of audiovisual records, both of the villagers in their daily lives and of my collaborators interacting with them, exploring the place, or intervening in sites with fabricated or found objects. El momento más hermoso de la guerra (2017) is the product of these records, a film that is one part of the film trilogy The Theater of Disappearance (2017), which encompasses the fleeting present of the projects.15

Figure 0.19

Figure 0.19 Figure 0.20

Figure 0.20This first experience in Yangji-ri in 2014 along with a small group of my collaborators, chosen on the basis of their social and communicative abilities, is the start of a close bond and prolonged engagement with the village residents. Together with the curators of the Real DMZ Project, our host, we decide to return regularly to visit them and make footage. This process will lead to a second film, The War of the Stars (2018).16 In 2016, a house recently vacated by its owner (a man who moved to his son’s home due to his advanced age) is acquired to deepen this sustained relationship with the village. Some of the man’s personal effects remain, like a pair of sandals and his actual footprints in the dust on the floor. Preserved as a humble and silent museum in his honor, these belongings and traces of the house’s former occupant become parts of a project that will function there, in his dwelling, in perpetuity. With a respectful housekeeping process, the space is prepared for future activities yet to be defined. Two cakes, baked by my team, are kept (perhaps forever) in a refrigerator in the kitchen.

Turning toward the Environment: Architecture as a Model for the Ecosystem “Project”

In Two Suns (2015, fig. 0.21), dozens of tiles, handmade in Rosario with leaves from trees, cigarette butts, seashells, coins, iPods, butterflies, glass, paper, and many other organic and industrial “residuals” inlaid in the cement, are transported to New York to cover the floor at Marian Goodman Gallery. Michelangelo’s David lies on that floor “asleep”: a scale replica of the iconic Florentine sculpture, with the physical posture modified to appear reclining, seemingly either defeated or dead. The David-tiles relationship is an attempt to contemplate the art-versus-background relationship, in other words that contiguous tension between the “work of art” and its context. Between that which carries the weight of being the human project (embodied in the David archetype) and what seems to be there to sustain that intention with its silence (and with its signage, its walls, its order, and its rules): the physical environment of the gallery, the museum, the institution. This is the architectural dimension of the problem of the environment, the negotiation for a redesign of the exhibition space as a part of the project, which, while earlier established in Lo que el fuego me trajo, is systematically attacked in Los teatros de Saturno and consolidates as a specific theme in Two Suns, The Work of the Ocean (2013),17 Fantasma, Planetarium, and the four projects of The Theater of Disappearance (2017).18

Figure 0.21

Figure 0.21In The Work of the Ocean (fig. 0.22), the entire interior of a house (kitchen, bathroom, living room, and bedrooms) is designed and built in the gallery in order to imagine an alternative life of some of the “suicidal” sculptures from dOCUMENTA (13) as small decorative statues made of epoxy putty (a highly durable material), and scenes from Brick Farm modeled from photographic records. The entire “home” is a silent location that acts as a neutral zone, as if it were an exhibition system of white gallery walls and bases, so as to create a semiotic trap: a comfortable and bourgeois environment resignifying sculptural objects as tasteful decoration, the originals of which (many no longer in existence) carry a dense burden of both conceptual and symbolic history as part of enormously complex processes.

Figure 0.22

Figure 0.22In Fantasma (fig. 0.23), the display devices usually used for museological exhibition are taken to their climax to show a series of surviving “mutants,” in a state of virtual mummification, from Los teatros de Saturno. These mostly organic items have been stored for almost a year at kurimanzutto gallery and are now transported to Moderna Museet in Stockholm in order to imagine a retrospective of my work in two hundred years—what these diachronic objects and other remaining evidence of my work would look like in the distant future. Being also a reflection on the notions of document, memory, and preservation, the project includes some suggestive found images showing the protection and evacuation tasks involving in saving artistic and cultural heritage in Europe during World War II, together with photographic registers documenting the recent dismantling in Buenos Aires of a statue of Christopher Columbus, the Spanish Italian navigator, and its replacement with a statue of Juana Azurduy, the Bolivian mestizo female South American independence war leader. The rooms are completely redesigned, with added walls, display platforms, and bases to house these surviving mutants and documents as well as the second life of “things” that were not originally “art,” but rather supplies in the production process, such as the pallets of the wooden boxes where the stratified cubes from The Evolution of God were made—now multicolored abstract landscapes because of the pigment absorbed by the wood. In other cases, display platforms house the second life of “things” that had been “art” in the now-disappeared sculpture installations, such as the cake-mountain from the Petrobras table, which my parents stored in a back corner of their business for almost a decade before it was transported to the Swedish capital using a sophisticated logistical plan and “revived” as a petrified mutant made of sugar, flour, fungus, and dust.

Figure 0.23

Figure 0.23In Planetarium (fig. 0.24, fig. 0.25), we clean, refurbish, and redesign an abandoned ice factory on the outskirts of the town of Kalba, on the edge of the Persian Gulf, in order to install a series of stratified columns made of pigmented plaster, clay, cement, compost, and organic and industrial products in that deconstructed space. These columns are directly derived from the Xochimilco “cubes,” both formally and technically, and in their function of chronotopic (time-space) crystallization. In addition to incorporating materials transported from other parts of the planet, like Xochimilco and the Brick Farm in Rosario, the components are brought together after an intense process of exploration and collecting in the Sharjah region. Indeed, it is this multidimensional immersion in the Emirate territory—involving geographic, socioeconomic, cultural, and human aspects—and the resulting interactions with a network of local contacts, that give me access to the Kalba waste treatment plant. This state-owned company, created to process the growing amount of garbage resulting from the region’s economic and demographic boom, is producing black dirt through a composting process for local agricultural use. One ton of this composted soil becomes a part of the landscape created with the ice factory, arranged into six mounds that encapsulate the expansion of the Capitalocene fertile frontier over the desert, based on the treatment of its own organic residue. Everything in Planetarium, as a system to absorb the environment or chronotopic crystallizer, suggests this anthropogenic conquest of the desert.

Figure 0.24

Figure 0.24 Figure 0.25

Figure 0.25This is how we come to The Theater of Disappearance, four projects in Bregenz, Athens, New York, and Los Angeles developed under the same umbrella title. In them, the various kinds of spatial, ontological, thematic, and procedural logics described above all come together, from transporting vernacular materials to exploring the environment, from reconfiguring the exhibition space to combining production methods from the different phases of my practice. A new variable is added to the language game: the human factor is removed from spaces that were heretofore essentially the province of manual work, such as sculpture, and replaced by digital modeling technologies such as a computerized robotic arm.

The Theater of Disappearance as Climax of One Era and Dawn of Another: Superfluous Humanity

Kunsthaus Bregenz in Austria, designed by the architect Peter Zumthor, serves as the setting for the culmination of the examination of art and exhibition space ties, as the project itself was the total redesign of the building’s four floors into a “home” for the staff that have looked after it since it opened in 1999. It is a kind of silent homage to those who, in the shadows, live to take care of this architecture. This homage is filtered through a melancholy look back at the Western notion of reason that feeds the museum’s unconscious. Text and context, work and environment, exhibit and exhibition spaces are all impossible to distinguish here, impelling the visitors to actually generate the boundaries between them, based on their movements and their sensory and hermeneutical activity (fig. 0.26).

Figure 0.26

Figure 0.26In addition to the usual array of vernacular materials from different parts of the planet, we incorporate granite containing four-hundred-million-year-old fossilized zooplankton extracted from the quarries of Erfoud and Rissani in Morocco. This granite was used to manufacture the tiles, flooring, and furniture used to remodel the museum’s interior. The almost imperceptible yet ubiquitous presence of this Paleozoic fossil contrasts (along the anachronistic and poetic path from a distant past toward the Western notion of reason that the exhibit traces) with the metonymic legs of Michelangelo’s David on a pyramid-shaped base on the upper floor, made from the same marble taken from the quarry in Carrara, Italy, that was used for the original sculpture.

In Greece, the National Observatory of Athens is the ideal setting for imagining the conquest of other planets from a disputed territory, no longer through war but symbolically. It is one of the premier scientific institutions in a country considered the cradle of Western civilization, but also a region that exists as a liminal zone between the Muslim East and the Christian West, recovered for “Europe” in 1832 after almost four hundred years of Turkish rule. Meanwhile, there in Athens, the nation’s historical identity and memory is defined by decisions made by the archaeological institutions regarding how deep to excavate to look for the “past”—which layers of earth to remove. Thus, reformulating the observatory’s exterior space, which is located on one of the seven Nymphs’ Hills where Athens is situated, and transforming it into a field of grasses (after obtaining complicated permits from the local archaeological authorities), as well as corn (an American crop), introduces the play of chronotopic juxtapositions addressing the problem of the appropriation of the ground, what lies beneath it or on top of it, by different countries, regions, and civilizations, with relation to the development of their economies and their identities (fig. 0.27).

Figure 0.27

Figure 0.27Argentina developed its foundation myth at the end of the nineteenth century, with the countryside as a binding marker for nationhood, and agricultural exports the only source of prosperity and integration with Western powers, much the way that modern Greece finds the material proof of its rightful place in that same cohort of “free nations,” claiming the Parthenon or the Acropolis as the nexus of that ideological and cultural matrix (fig. 0.28). For both countries, the soil, on its surface or in its depths, in its material or historical wealth, plays a central role in their connection to the “civilized world.” It is also in the soil that, with the early beginnings of agriculture and sedentism, more specifically the growth of grasses such as wheat ten thousand years ago, we find the key to the development of ever more complex human groups: city-states, kingdoms, empires, nation-states, and, finally, the modern global societies of advanced techno-capitalism that must now seek new inhabitable territories outside Earth, just as in other eras when arable land expanded, swaths of desert or sea were won, continents were conquered, or new commercial routes were created. But now the issue is no longer attempting to grow; it is attempting to survive the catastrophe of growth.

Figure 0.28

Figure 0.28One last detail brings the telluric cycle full circle in the Athens project: while beneath that city the ruins of one civilization lies under another, providing ample material for archaeology and anthropology, Argentina’s tendency has been to see its ties to the land as a connection with a young fertile uterus, almost without history. And yet it is layered with the remains of the megafauna that inhabited the subcontinent until seven thousand years ago. Besides, Jurassic fossils feed a national paleontology that even has a blockbuster star: the Argentinosaurus, the largest dinosaur ever unearthed. Two debts to truth and justice, however, still lie buried beneath that soil: the genocide of the Indigenous peoples (the Argentine territory’s former expropriated owners) and the disappeared of the last military dictatorship (1976–83). Over the past few decades, there has been increasing will to settle those debts. Forensic anthropology is playing a key role by collaborating to identify the skeletal remains found in NN (from ningún nombre, or no name) tombs and graves, or even in museum anthropological archives, as is the case with the Museo de La Plata of natural science, where the Grupo Universitario de Investigación en Antropología Social (GUIAS, or Social Anthropology Research Group) uncovered more than ten thousand human remains, as well as in other museums in Germany, France, and England that were beneficiaries of that institution. The remains belonged to more than two thousand five hundred unidentified people murdered during the extermination and expropriation of Indigenous peoples by the Argentine state, known as the Conquest or Campaign of the Desert (1878–95). In the Athens chapter of The Theater of Disappearance, this accumulation of questions surrounding the complex problem of the soil is laid out on the carpet.

In the New York chapter, the rooftop of the Metropolitan Museum of Art becomes the setting for an examination of the compartmentalization of “world history” based on a white Eurocentric paradigm, and for the possibility of its deconstruction, starting with a counter-hegemonic geopolitical-poetic reorganization. Following a several-months-long process of research and selection in the different departments (Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, Greek and Roman Art, Medieval Art, the American Wing, et cetera), I arrive at a kind of convulsion of official chronological, geographic, ethnic, and cultural divisions.

Three-dimensional scans are taken of hundreds of pieces from the collection—frequently of objects on the peripheries of the departmental canon, such as utensils or everyday tools. They are reactivated in new sculptural combinations modeled via a 3D milling process (a robotic arm), along with human figures derived from scans of real people. The goal is to present these new objects in a “living” way, bound to the body, the head, and the hands—returned to their ordinary function as “tools for life” that exhibition display systems (cases, supports, tempered glass) often negate or hide as they follow security and conservation protocols. It is also a response to the fetishization of materials that operates in the unconscious of these institutions. These new sculptural forms are displayed on the Met rooftop, on top of and in between large tables with tablecloths and place settings, as if served for a bacchanal that the public can move through, activating their own ritualistic, festive, hedonistic, and even anthropophagic fantasies (fig. 0.29). It is, pure and simple, an attempt to reactivate the frozen materiality of the museum.

Figure 0.29

Figure 0.29A not-insignificant detail: the sculptures presented at the Met no longer respond to the artisanal and suicidal logic. They are fully produced by a robot and made of materials such as nylon and polyurethane: highly resistant and durable plastics. We flip the poles of the temporal paradox that was laid out in the “suicidal” phase, and which very broadly consisted of representing the present and the distant future using techniques from the past and perishable materials. Here, humanity’s distant past, thematically reactivated with these pieces, is approached technically using tools from the future and ultra-resistant materials, in processes where the intervention of the human hand has virtually disappeared. Compared to earlier periods in my practice, and even more so with the objects chosen from the collection, we are dealing with an “art” that can well correspond to a phase characterized by a “superfluous humanity”: replacing muscle, nerve, and brain with artificial intelligence. As such, the project as system to absorb the environment takes another step forward, risking a certain poetic hypothesis about the future that, not coincidentally, is unfolding on the museum rooftop.

The chapter of The Theater of Disappearance at MOCA in Los Angeles also presents an examination of this “superfluous humanity” that techno-capitalism seems to be heading toward (along with new forms of semi-enslaved work in regions with exceedingly low levels of unionization, workers’ rights, and salaries, such as South Asia, Africa, and Latin America). This time it is seen from the perspective of the new digital technologies used by Hollywood to create its super-productions, connecting the blue screen or green screen in California studios with the so-called render farms in countries like China, India, or Pakistan, where thousands of outsourced workers cut out silhouettes of movie stars to insert them in computer-designed locations. On the final frontiers of this radical replacement of the analog by the digital in the movie industry, articulated dolls are literally built with images and sensors from a package of key movements and gestures belonging to the actor or actress, doing away with the need for fully acted sequences from the script. In this sense, superfluous humanity in the Western metropole has its counterpart in the superfluous humanity of the periphery or factory countries.

The use of blue screens as a leitmotif and framework for the objects presented at MOCA signals this white noise that Hollywood film has become, where the actors, connected to mobile sensors, isolated from their environment and above all from other actorly connections, perform a series of disconnected movements in front of a neutral backdrop, which will later be hyper-processed in a render farm somewhere in South Asia, where they will be virtually transformed into video game characters who become the real stars of the movie. Like actors with no future, submissive to whatever may come, the “things” presented against the blue screens in the central spaces of the museum not only absorb the myriad elements collected in the very intense months-long explorations I made in California’s “innovative milieu” and leafy stores of cinematographic junk; they also incorporate the remains of earlier projects and vernacular materials, gathered over years, stored in rental warehouses and brought from various corners of the planet, involving the largest logistical operation to date in my practice. Stones from Turkey, wood from Turin, marble from Morocco, flora and fauna from Mexico and Argentina, stratified columns, and even a bicycle wheel found along the shore in Sharjah all arrive in Los Angeles to blend alchemically with the organic and industrialized local materials (fig. 0.30). An enormous polymorphous mutant, a Leviathan project, rises up on the West Coast of the United States.

Figure 0.30

Figure 0.30One last point that encapsulates the pivotal nature of the Californian iteration of The Theater of Disappearance in relation to the key elements and dynamics of this period is the total absorption of the exhibition space as a decisive part of the system. It is a transformation the likes of which I have never attempted before, after facing together with its curatorial authorities such profound deconstruction of MOCA’s physical-institutional space that it almost caused the entire project to collapse. The architecture of the space is operated on to elicit a true ecosystem, capable of hosting a macro-project that is absorbing virtually all of my previous projects. Stairways and ramps are removed. Floors are leveled. Walls and banisters are taken out. The lighting is modified. Offices, bathrooms, and hallways are moved. There is not a single element of the building that is not part of the project, whose sovereignty over the space is reticular. In that way an Aleph, a point that is all points, a chronotopic crystallizer of my entire project-life, happens temporarily in Los Angeles, that Western cradle of the fiction of the masses, at a critical junction of its own transformation, where the prospect of disappearing or sharing arable land with new species of “grasses” planted in Silicon Valley is being debated. Google, social media, Netflix, apps—all of them are, perhaps, new forms of fiction.

Conclusion: The Long Road from the Work of Art to the Garden of Forking Paths

Ever since my years as a student at the Escuela de Bellas Artes in Rosario, I understood that contemporary art was something that could not last forever. On the contrary, I intuitively knew that a central problem was its very disappearance, its speed, and its superabundance, which in fact made it insignificant. That insignificance resulting from overproduction clashed with the will to survive and to transcend that all things have, especially humans. Adopting the fictional gaze of an alien from another world, looking from a distance with an icy horizontality, I threw myself into working with that physical and metaphysical tension that has time as its central and agonizing question, but also as its great tool.

All things are beings in time, straddling life and death, the ephemeral and the eternal, the present and its incessant pull in opposite directions: toward the past and toward the future. The entities that I have designed attempt to access some of that existential tension of Dasein, and as such are positioned, singular and unrepeatable: they are not being, they are happening. The early appearance of the organic in my practice in the form of clay gave me the material basis to think of their corporeality as a happening, as the fleeting present doing battle with entropy. That was combined with a dynamic of work (my team) and movement (nomadism) in environments that demanded ever-greater immersion and commitment. It was not long before time became space-time. The space-time of the Other.

With this article, I have attempted to create a descriptive record of how living matter exists in my practice, understanding not only the presence of a certain organic materiality, but more precisely the complex connection between work, auto-production, and environment via a chronology that spans from the suicidal sculptures (the clay + cement period that results in a programmed disappearance), to the diachronic objects, hybrids, or mutants (incorporating new organic and industrial components that reinforce autopoiesis and deprogrammed growth), to arrive at the notion of the project as a system to absorb and be reabsorbed by the environment (deep immersion in local contexts that ends up in a chronotopic crystallization), and lastly, as ecosystem (the emergence of a new ecological balance through housekeeping and the negotiated redesign of the architectural-institutional space).

In relation with these transformations of the object, I have attempted to demonstrate their correspondence with a simultaneous transformation of the subject—that is, of the organization of my team’s collaborative work, which spans various phases (community of builder-sculptors, itinerant company, workstations) to arrive at what is currently a range of available organizational forms in conjunction with the incorporation of new technologies like rendering, three-dimensional scans, and the robotic arm, complicating the systemic equilibrium of living matter: the latent threat of superfluous humanity.

Within this framework, I have presented a series of projects that, when linked, serve as hinges in the progressive emergence of a new paradigm, from hibernation in raw clay (2008–13) to the blossoming of a “garden of mutants” in an unpredictable forking of paths beginning in 2012 with Brick Farm, and its effect on Today We Reboot the Planet. This anomaly became law in Los teatros de Saturno and Xochimilco, which marked the consolidation of a phase characterized by organic material as the organizing factor of an extended (diachronic) temporality, and by the withdrawal of human agency in favor of other modeling forces. In this phase, there was a shift from time as representation to time as sculptor, not only stemming from entropy (the principal nonhuman agent of the previous period) but also from auto-production, which provokes another shift, this one from the idea of “completion” to the idea of “horizon,” a never-ending process of self-modeling from inside out. This constant self-modeling via growth and decay opens a new stage that follows the end of the human part of the projects, that of monitoring of the autonomous life of the diachronic objects by the institutions that house them and my office. This led to examinations such as the one in Motherland, touching on the “eternal” link that ties us to institutions in charge of mutant objects, or like that of Fantasma, where I attempted to imagine a retrospective of my work in two hundred years.

Furthermore, I have attempted to demonstrate how the transporting of vernacular materials, fragments of projects, and residual team energy from one point of the planet to another in order to be recycled into subsequent projects stemmed from that same nomadic dynamic, and from the accelerated speed that was a result of the hyper-entropic nature of the system. That system has sought to perpetuate itself more through action (with the communal geneticization of a language aimed at “doing”) than with “done” materiality, and through creating a record of that fleeting present with poeticized archives, pictorial homages to studio activities,19 or films based on audiovisual records with varying degrees of cinematographic self-awareness.20 The publication of texts such as this article, catalogues, and artist’s books, which are currently in production, is a fourth source of records.

Accordingly, my objective here was to examine how the material dimension of my practice is more the precarious act of bearing witness to an activity that is lost forever (all of the richness of a nomadic life in that community or of the processes of exploration) than the ultimate goal of a “career” aimed at producing commodities. That is why the environment, first in the form of an immersive process that led me to develop a geopolitics of friendship, with strategies for respectful connections with different local realities and the actors who experience them, and next in the form of housekeeping within physical and institutional spaces with the goal of reaching a singular and unrepeatable ecological equilibrium, was posited here as the final stop on a journey that aspires to constantly escape the work of art and move toward the thing, long oblivious to its condition as fetish, and that, without labels or proper nouns, surrenders completely to bare life. It is there, at that point, where matter becomes, in the end, living.

Notes